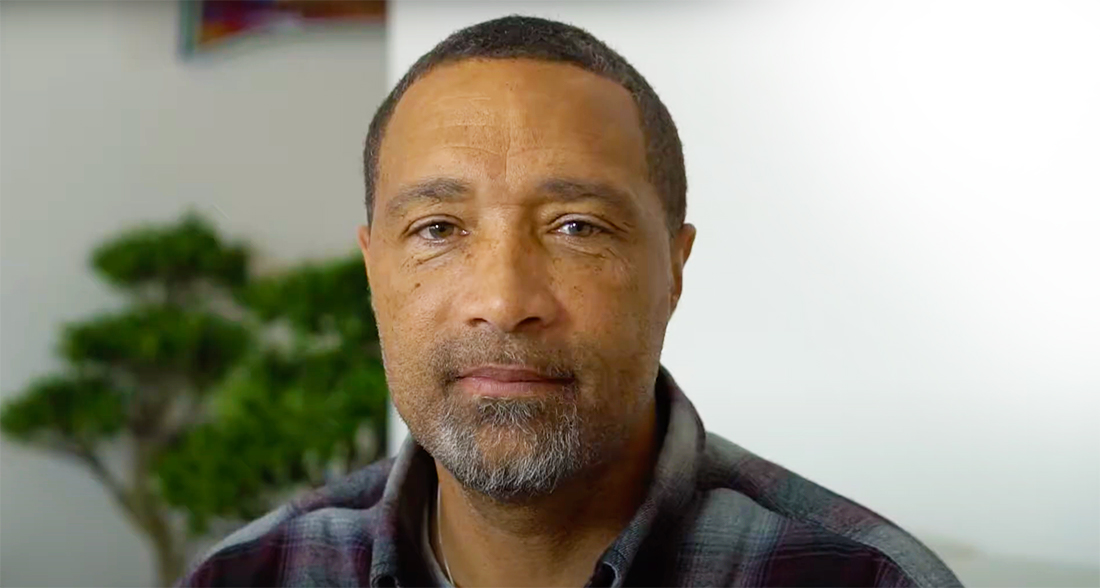

Mataka spent 23 and a half years behind bars for a non-violent drug crime. He’s now using that experience to help others. He defines himself by being an educator, advocate, and devoted father. His antidote to trauma and stress: peace. How did he find peace post-incarceration?

Post-incarceration syndrome doesn’t start in prison. It starts pre-incarceration with trauma. Mataka Askari grew up in St. Louis in what he describes as a predominantly impoverished community.

“Poverty breeds despair and despair breeds criminality,” says Mataka. “Not everyone there is engaged in crime, however, poverty drives the mindset of ‘let’s see how we can get this money’ so the strongest influence in the community at that time was criminal activity. I had no influence from the other side that would have guided me down the right path. The influence overwhelmed me. I was involved in the criminal justice system since I was 14 years old.”

In 1995, Mataka received a 30-year prison sentence for a non-violent drug crime. He spent 23 and a half years behind bars. He’s now using that experience to help others. Mataka defines himself by the lessons he’s learned, being an educator, advocate, and devoted father. He discovered his antidote to trauma and stress: peace. How did he find peace post-incarceration?

Mataka explains that complex trauma drives behavior, which leads to high recidivism rates, which leads to people re-engaging in criminal activity. These behaviors are often the result of coping mechanisms born out of the need to survive trauma.

So while in the prison system, Mataka had a lot of time to reflect on his behavior. “Why did I commit a crime? Why was I thinking that way? I was acting out of a form of information that was not conducive to bringing out the best in me.”

Mataka picked up a book that would change his life forever: The Autobiography of Malcolm X. While reading this, Mataka realized that he had internalized some unhealthy ideas and images about himself. He started studying psychology, religion, and politics, driven by a process of self-discovery. Through that process, he began to detox from those negative thoughts and ideas.

After being released on August 24, 2018, Mataka knew he didn’t want to live his life in his 40s like he was living in his 20s. “I did not want to live in arrested development.”

Being out of the prison system brought some unexpected challenges. “I started experiencing some things that I did not experience before I went to prison.” Mataka noticed. For example, one night, he and his wife Erica went out to see a movie. “I kept looking around to assess my surroundings and I see some people in hoodies. I started thinking something was about to go down in this movie theater. I told Erica and she said, ‘Mataka, they’re wearing hoodies because it’s cold in here.’ I had paranoia from being in an unfamiliar environment.”

Mataka also had difficulty sleeping. He couldn’t fall asleep and when he did, he had a hard time staying asleep. Slight sounds would startle him.

Erica researched and discovered post-incarceration syndrome (PICS). When she brought it up to Mataka, he rejected it.

“I’m a Black man from the north side of St. Louis–I don’t want to hear about no trauma or mental health issues or none of that. I came from a community where if you came across a problem, you pushed through it to the other side.” Mataka explained. But the more he experienced it, the more he wanted answers.

Mataka noticed more symptoms. He had hypervigilance. He felt a chronic sense of helplessness due to living a lifestyle without many choices in prison. Living in a cell for so long gave him a sense of security because he knew his space and didn’t have to worry about seeing around corners.

He had an exaggerated startle response. Mataka explained that in prison, there were unspoken rules. You don’t get too close to people. Out in the real world, people would brush past you or invade your personal space. It made him feel unsettled.

“I felt like something was out to get me. Did I have old enemies or would I fall back into the same cycle of behavior and self-sabotage again and go back to prison?” He had to come to terms with his PICS.

He had been dealing with those feelings for a long time. He turned to literature once again for answers and understanding. He turned to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic Statistical Manual) to study trauma and stress-related illnesses. Mataka started reading about sanctuary trauma, multigenerational trauma, cultural trauma, and complex trauma.

“I realized that I lived in a society that normalizes trauma. We operate on a facade where we create this impression, but then when we get away from societal view, we start engaging in unhealthy coping mechanisms and it brings toxicity into your life in the form of relationships with your partner, your parenting, even into your employment. When we don’t know how to identify and deal with trauma in a society that normalizes it, then we operate in a state of dysfunction and you can only do that for so long before things blow up.”

He illustrates his point by comparing it to an illness. “If you have a cold and one symptom is a fever and your fever gets to 105 degrees, you know you have to treat the symptom because it has become so bad that the symptom is a threat to your life. But it’s not the underlying cause. So when we see our lives taking a turn for the worst and we engage in unhealthy coping mechanisms and self-sabotage and expressions and outlets–these are symptoms. What is the cause? The cause is trauma. The things we still remember in our minds is what’s driving our behavior 10, 20, 30, 40 years after they happen.”

Now, armed with a wealth of information that gave clarity to his own experience and others, Mataka began to think about how to establish optimal mental health away from the trauma and stress.

“The antidote to stress is peace,” Mataka explains.

We live in a society that is so overwhelmingly stressed. On top of that, we have unresolved issues that trace all the way back to our childhood. We just accept it as normal and deal with it in our own way.

“If you have these issues, this brokenness–what are you going to convey to the generations that come after you–your children, your grandchildren? We have to interrupt the cycle and introduce ways to achieve peace and bring our best selves to the world,” he explains.

Mataka recalls how much joy and escape that reading brought to him, especially when he was locked up.

“You know what I noticed? Life does not allow you the leisure time to read that prison does because you have life responsibilities. But let me tell you what I understand: In prison, there are still drugs. You can still engage in unhealthy coping mechanisms. You can get high but when you come down from that high, you still have the same problems so it drives you to look for relief. But for me, the thing that got me through to make myself a better person was reading. I realized that with a book I could take my mind anywhere I wanted to take it. I could achieve ‘highs’ but when I came down from that high, I brought something with me: the ability to take my mind to a different place and bring back the information with me to make myself a better person. That’s what got me through it.”

Mataka has a solution to help bring forth peace. It involves reading, visualization, and even integrating technology.

“Peace is achieved through conjuring up or having images in your mind because we think in words and pictures. We have our intelligence and our imagination. What’s the root word of imagination? Image. Visualization. How can we put in our minds the imagery that brings that natural peace inside of us to the surface and allows us to reach a relaxed state to combat the stresses and traumas of life?”

“Trauma isn’t just psychological. It alters your brain and your biochemistry. Scientists have shown how it impacts your brain structure, your digestive system, your overall health; and it’s been proven that people who live under functional trauma live 20 years less than people who don’t live under functional trauma.”

“If you have devices, like Healium, that give you visual imagery of peace, then that peace allows you the stability to move forward. These things are necessary because when you have these images or these devices that can assist you in achieving a state of peace not only does it do more for bringing out the best part of you and putting you in a state of relaxation–it extends your lifespan. What Healium has been able to do is tap into this technology that allows us to combat the most toxic thing that faces the family right now: trauma and stress.”

Further driving home his point about how images impact your brain, Mataka reflects on the current state of our media and maintaining a healthy media diet.

“The media gives us images. These images have dominated and saturated our minds in such a way that they pull the best part of us down and have us believe that it’s going to be impossible to change. So we just accept it and we move through this life thinking we’re incapable of doing anything and we accept things that we know are not right and we compromise ourselves. Any time you compromise yourself and you are not able to be you, it acts in a negative way on your being.”

By removing your exposure to these negative images and replacing them with empowering, uplifting, and positive ones, you can begin to reprogram your brain. Mataka goes one step further and stresses the importance of nurturing all of the senses as well.

“Multiple senses bring information to the brain. We taste, smell, feel, hear things that can help us bring peace to the brain, and transform your internal being.” Mataka says.

He focuses so heavily on starting within because you can’t help others until you heal yourself. The health of the individual is necessary for the health of the community. You can begin to transform the people in the environment in a positive way. However, the opposite is also true.

“Remember MLK said ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ One thing that’s toxic has the ability to make the whole environment toxic if it’s left unchecked. So if we’re operating in a toxic way, what do you think we’re bringing to the world? We owe ourselves peace and the ability to live our lives in the best way possible. We owe our families the ability to get the best of us. We deserve an opportunity to be happy.”

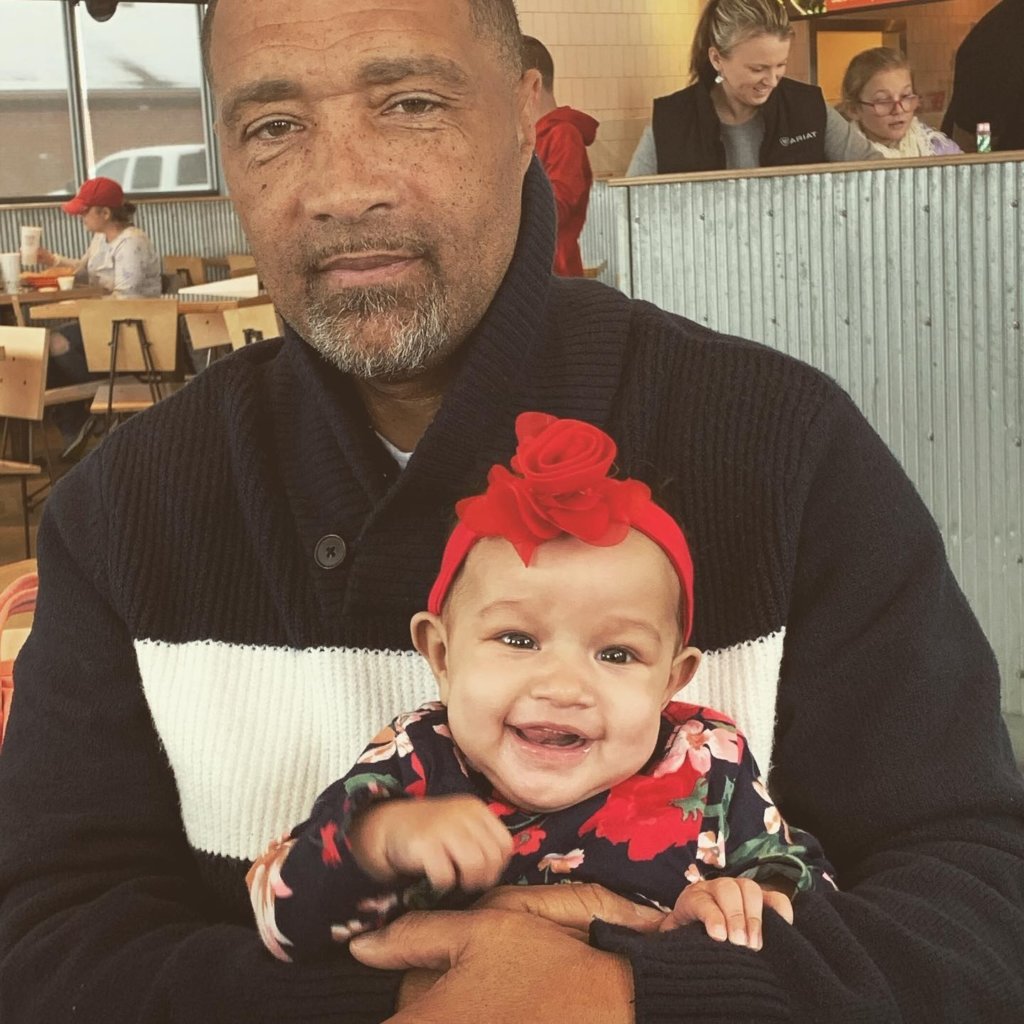

What does the future hold for Mataka Askari? Being a devoted father to his daughter is a huge motivator for him. He wants to empower her to have her own legacy. It’s that kind of forward-thinking that has enabled him to transform his life.

“I want to be the best father for her. Not just financially, but I want to equip her with an understanding that does not allow her to fall victim to self-doubt or influences that make her question her worth or her value for things that have no merit. I want my daughter to bring to this world the best part of her so that her legacy can be one that is enduring.”

His philosophy for his daughter and his community to thrive is through a strong education. “I’m a huge proponent of proper education. The word education comes from the word educe which means to draw out. It’s not necessarily a bunch of pouring in of information that makes you think along a particular path. But what it means is having a system set up to have your greatness and potential to be drawn out and unleashed onto the world in the best way possible. So I’m a proponent of whatever unlocks, uncovers, unburies, and removes every obstacle out of your way that impedes your ability to be the best you. It’s scientifically, theoretically, and otherwise impossible to be the best you when you’re under trauma and stress.”

At the beginning of Mataka’s story, he talked about how he had internalized unhealthy images and ideas about himself. He knew that to bring peace, he had to detoxify himself from those negative images and replace them with healthy ones.

His antidote to stress is peace. Mataka leaves us with something to reflect: “Even with all of these things that we’re out here doing–running businesses or helping feed families–the most important thing is, what legacy are you leaving? How are you leaving the world? Are you leaving it better than when you came in?”

You can connect with Mataka Askari on Facebook and/or through email at matakaaskari@gmail.com.

You can connect with Mataka Askari on Facebook and/or through email at matakaaskari@gmail.com.